Originally posted on the Dental Elf

Question:

Which gown/apron combination provides the best protection in the dental practice?

Bottom-line answer:

From this reanalysis of the primary data the reusable cotton surgical gown may be more practical in the dental environment in the long-term than the disposable fluid resistant gown due to its reduce potential for cross contamination during use. The plastic apron creates the most cross contamination and should only be used if there is significant risk of fluid contamination.

Background

This paper is a reanalysis of a recent systematic review (Verbeek et al., 2020) on personal protective equipment (PPE), reframing the question to fit into the new clinical workflow created by Covid-19, and dental aerosol generating procedures (AGPs). I have covered face masks in a previous post.

Much has been written on the epidemiology of Covid-19 and its transmissibility via contact, droplets, aerosols, or faeco-oral route. The main concern within dentistry being the aerosol generated during many routine dental procedures (Coulthard, 2020). To reduce this contamination risk Public Health England’s guidance document for personal protective equipment updated 3 May 2020 Section 10.4 (GOV.UK, 2020) states that:-

‘Disposable fluid repellent coveralls or long-sleeved gowns must be worn when a disposable plastic apron provides inadequate cover of staff uniform or clothes for the procedure or task being performed, and when there is a risk of splashing of body fluids such as during AGPs in higher risk areas or in operative procedures. If non-fluid-resistant gowns are used, a disposable plastic apron should be worn’.

As this advice is generic and the workflow within a critical care unit differs from a dental practice it is important to evaluate the best available evidence from a primary care rather than secondary care perspective.

Method

To save unnecessary duplication of search strategies and risk of bias/quality assessments I utilised the most up to date Cochrane Review of PPE for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff (Verbeek et al., 2020). This systematic review included 17 studies with 1950 participants evaluating 21 interventions. The authors concluded:

‘We found low- to very low-certainty evidence that covering more parts of the body leads to better protection but usually comes at the cost of more difficult donning or doffing and less user comfort, and may therefore even lead to more contamination. More breathable types of PPE may lead to similar contamination but may have greater user satisfaction.’

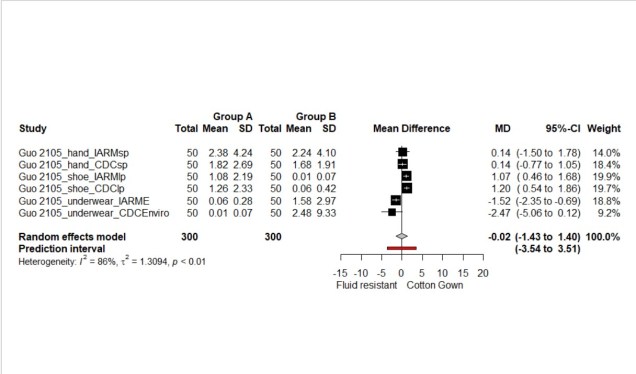

The authors conclusion helped to focus the next stage of analysis which was based around the levels of contamination and wearability. From the included studies two randomised simulation trials, one of a parallel design (Wong et al., 2004) and a second of a cross-over design (Guo et al., 2014) were selected as they contained sufficient primary data to undertake a meta-analysis. A simulation trial utilises aerosolised fluorescent dye sprayed on the PPE instead of true viral contamination. It was possible to extract data on contamination of fluid resistant disposable gowns, standard cotton surgical gowns, and plastic aprons. The data was placed in Excel and then transferred to R for meta-analysis using the ’meta’ package. A random effect model was used with a Hartung Knapp conversion due to variability within the studies. Prediction intervals were included to facilitate the estimation for future studies.

Findings

The first meta-analysis compared a fluid resistant disposable gown with a standard cotton gown for both Wong and Guo. In Guo’s study the group tried two methods of doffing PPE: their individual accustomed removal method (IARM), and gown removal methods recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The overall result favoured the cotton gown, but the result was non-significant, the mean difference (MD) was 0.91 (95%CI: -0.34 to 2.66) (See Figure 1.). The second meta-analysis showed significantly less contamination of the cotton surgical gowns compared with the plastic apron, the MD was 8.4 (95%CI: 0.59 to 16.2) (See Figure 2.). The final analysis looked at the contamination of the clinician post PPE removal showing equal contamination between the different PPE types MD was -0.02 (95% CI: -1.43 to 1.40) (See Figure 3).

Figure 1.Forest plot of disposable fluid resistant gown vs cotton gown

Figure 2. Forest plot of plastic apron vs cotton gown

Figure 3. Forest plot of body contamination

Conclusion

From the results of the meta-analysis there is little difference between the disposable fluid resistant gown and the reusable cotton surgical gown in terms of contamination/protection of both the wearer, patient, and clinical environment. The results favour the cotton gown as cotton through its material and properties can absorb droplet contaminants and thereby reduce opportunities for such contaminants to spread to the environment. The plastic apron performed worst and may significantly increase the risk of cross contamination both to the clinician and patient and should only be necessary where there is a risk of serious fluid contamination.

There is an interesting paper recently published by Phan and co-workers (Phan et al., 2019) who observed that ‘90% of observed doffing was incorrect, with respect to the doffing sequence, doffing technique, or use of appropriate PPE. Common errors were doffing gown from the front, removing face shield of the mask, and touching potentially contaminated surfaces and PPE during doffing’.

These results presented are hypothetical and due to the lack of specific studies of virus penetration through gowns in dentistry and are based on surrogate, and composite outcomes. There is an urgent need for specific studies to address PPE performance in the dental surgery environment.

Disclaimer: The article has not been peer-reviewed; it should not replace individual clinical judgement, and the sources cited should be checked. The views expressed in this commentary represent the views of the author and not necessarily those of the host institution. The views are not a substitute for professional advice.

References

COULTHARD, P. 2020. Dentistry and coronavirus (COVID-19) – moral decision-making. Br Dent J, 228, 503-505.

GOV.UK. 2020. COVID-19 ( personal protective equipment (PPE) [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control/covid-19-personal-protective-equipment-ppe [Accessed].

GUO, Y. P., LI, Y. & WONG, P. L. 2014. Environment and body contamination: a comparison of two different removal methods in three types of personal protective clothing. Am J Infect Control, 42, e39-45.

PHAN, L. T., MAITA, D., MORTIZ, D. C., WEBER, R., FRITZEN-PEDICINI, C., BLEASDALE, S. C., JONES, R. M. & PROGRAM, C. P. E. 2019. Personal protective equipment doffing practices of healthcare workers. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 16, 575-581.

VERBEEK, J. H., RAJAMAKI, B., IJAZ, S., SAUNI, R., TOOMEY, E., BLACKWOOD, B., TIKKA, C., RUOTSALAINEN, J. H. & KILINC BALCI, F. S. 2020. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 4, CD011621.

WONG, T. K., CHUNG, J. W., LI, Y., CHAN, W. F., CHING, P. T., LAM, C. H., CHOW, C. B. & SETO, W. H. 2004. Effective personal protective clothing for health care workers attending patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. American journal of infection control, 32, 90-96.