Bottom line

Even though handheld infrared thermometers are convenient to use to check if a patient has an elevated body temperature, they aren’t sufficiently accurate for screening purposes. Using recent Office of National Statistics data on the prevalence of Covid-19 in the population the false positive rate is too high (>95%). The major confounders regarding accuracy are environmental temperature, humidity, gender, exercise, and age.

Background

In the recent Cochrane ‘Recommendations for the re-opening of dental services: a rapid review of international sources’(Cochrane, 2020) some of the guidelines recommended temperature screening of the patients at reception for elevated body temperature. The rational being that if a patient is infected with Covid -19 the body’s response to the virus often results in core body temperature increase. Traditionally body temperature was taken with a glass/mercury or electronic thermometer that required intimate contact with the patient but now there are handheld infrared thermometers (HIRT) that are quick and require only skin contact via the ear canal, or contactless by measuring the forehead skin temperature. In this opinion paper we aim to find out how effective temperature screening is in detecting Covid infected patients.

Methods

To reduced unnecessary searching through the literature to answer this question the diagnostic accuracy data was extracted from two rapid reviews, the most recent from the Emergency Care Research Institute (ECRI, 2020), and the second from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH, 2014). It was possible to extract the sensitivity and specificity data for 10 studies measuring the effectiveness of HIRT for forehead temperature (FT), and 7 studies measuring ear (tympanic) temperature (TT). The data was extracted and back transformed into a classic 2×2 table giving us the true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP) and true negative (TN) data and meta-analysis was carried out using the ‘mada’ package in R. The summary estimate for sensitivity and specificity for TT and FT are tabulated below (See Table 1).

Table 1. Summary estimates for IR thermometer

| Measurement location | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Tympanic temperature | 78.7 (95% CI: 69.4 to 85.8) | 91.8 (95% CI: 75.7 to 97.6) |

| Forehead temperature | 51.1 (95% CI: 19.3 to 82.0) | 97.1 (95% CI: 92.2 to 99.0) |

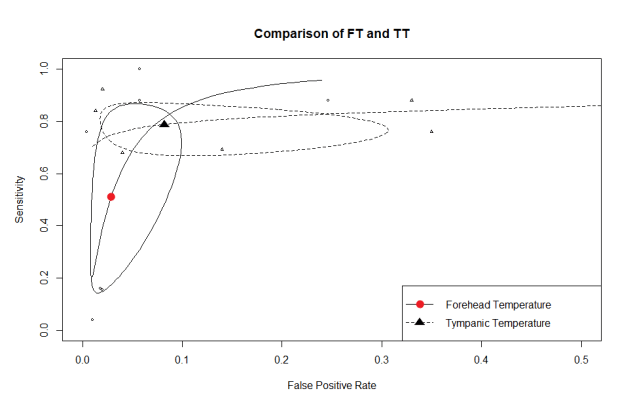

The results for the TT and TF results were plotted together on to a Summary Receiver Operating Characteristic (sROC) curve for comparison. The y-axis represents the sensitivity (1.0 =100%), and the x-axis represents 1- specificity (0.1 = 10%), the solid triangle and circle are the summary estimates, and the ellipses are the 95% confidence areas. ( Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy tests

A perfect diagnostic test would be in the extreme top left corner representing 100% true positives and 0% false positives and from the chart we can see that point is outside the 95% confidence area meaning that both tests are poor for screening. To clarify this point I transformed the sensitivity/specificity results into a frequency tree (Figure 2) using a diagnostic test calculator (http://araw.mede.uic.edu/cgi-bin/testcalc.pl)

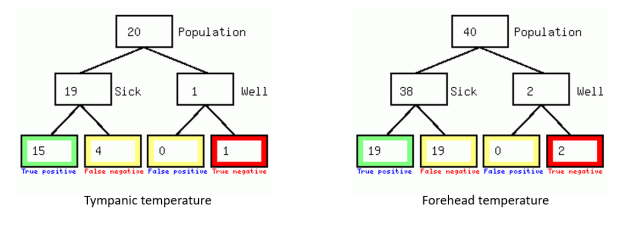

Figure 2. Frequency trees for diagnostic tests for screening Covid-19 (Prevalence 1:400)

If these thermometers are used for screening patient for Covid infection then out of every 838 patients who test positive with elevated TT only 20 will be infected which corresponds to a probability of 2.4% and for the FT that rises to 4.2%.

What happens if we use these thermometers to confirm a diagnosis of fever where we set a prevalence of 95% instead of 0.0025% (Figure 3.).

Figure 3. Frequency trees for diagnostic tests to confirm fever

Conclusions The authors of the recent ECRI report concluded:-

Temperature screening programs using IR alone or with a questionnaire for mass screening are ineffective for detecting infected persons, based on our review of evidence from 2 large systematic reviews (SRs), 3 simulation studies, and 6 diagnostic cohort studies (not included in the SRs). Under best-case scenarios, simulation studies suggest such screening will miss more than half of infected individuals. They are ineffective for mass screening because of the low number of infected individuals who have fever at the time of screening and inconsistent technique by operators.

Comments

Both pieces of diagnostic equipment produce highly variable results whether used for screening or confirming a diagnosis of febrile illness. The limitations are well described in the CADTH report (CADTH, 2014):

The retrieved studies have mentioned potential confounders for measure of temperature such as sweat, gender, age, the range of temperature, the rater, physical activity, the use of antipyretic drugs and emotional state. These factors are even more susceptible to vary in a real world conditions than in a clinical study setting. Moreover, the different brand/model/mode of devices used make it difficult to draw general conclusions on a class of thermometers. Also, a fair number of pediatric studies were included in the present review, limiting the extrapolation of their results to a general population.

In conclusion if a patients temperature needs to be taken then tympanic temperature is more reliable than forehead temperature, however its use for screening in the practice creates another layer of complexity in the cross infect/record keeping process with little diagnostic value.

Disclaimer: The article has not been peer-reviewed; it should not replace individual clinical judgement, and the sources cited should be checked. The views expressed in this commentary represent the views of the author and not necessarily those of the host institution. The views are not a substitute for professional advice.

CADTH. 2014. Non-Contact Thermometers for Detecting Fever: A Review of Clinical Effectiveness [Online]. Available: https://www.cadth.ca/infrared-thermometers-detecting-fever-clinical-effectiveness [Accessed].

COCHRANE. 2020. Recommendations for the re-opening of dental services: a rapid review of international sources [Online]. Available: https://oralhealth.cochrane.org/news/recommendations-re-opening-dental-services-rapid-review-international-sources [Accessed].

ECRI. 2020. Infrared Temperature Screening to Identify Potentially Infected Staff or Visitors Presenting to Healthcare Facilities during Infectious Disease Outbreaks [Online]. Available: https://www.ecri.org/covid-webinar-infrared-temperature-screening-reduce-infection-transmission/ [Accessed].

Disclaimer: The article has not been peer-reviewed; it should not replace individual clinical judgement, and the sources cited should be checked. The views expressed in this commentary represent the views of the author and not necessarily those of the host institution. The views are not a substitute for professional advice.

As we can see even in a simulation study, we are going to have to at least place over a hundred individuals in each arm of the study. To see if the benefit translates into the real-world, we need to go up two orders of magnitude to see if there is a significant difference between perfect and good PPE based on accurate population base-rate figures.

As we can see even in a simulation study, we are going to have to at least place over a hundred individuals in each arm of the study. To see if the benefit translates into the real-world, we need to go up two orders of magnitude to see if there is a significant difference between perfect and good PPE based on accurate population base-rate figures.